Biomechanics/Neuromuscular

(3) STRENGTH-DEPENDENT DIFFERENCES IN DOWNWARD PHASE DURATIONS DURING ACCENTUATED ECCENTRIC LOADED AND TRADITIONAL BACK SQUATS

.jpg)

Adam Sundh, MS, CPSS*D, CSCS*D, USAW-2

Sport Scientist Assistant

Chicago Bears Football Club

Lake Bluff, Illinois, United States.jpg)

Conor J. Cantwell, MS, CSCS*D, USAW-1

Assistant Strength & Conditioning Coach

University of Wisconsin - Platteville

Platteville, Wisconsin, United States

Brookelyn Campbell, MS

Coordinator of Sport Performance

University of Houston

Oconomowoc, Wisconsin, United States- LM

Lauren Marshall

Sports Performance Coach

Movement Fitness

Rockford, Illinois, United States

Zach S. Schroder, CSCS, USAW-1

Head Strength and Conditioning Coach

Morningside University

Sioux City, Iowa, United States

Jack B. Chard, M.S (he/him/his)

Baseball Strength and Conditioning Specialist

BRX Perforamnce

Waukesha, Wisconsin, United States- CT

Christopher B. Taber

Associate Professor

Sacred Heart University

Fairfield, Connecticut, United States

Timothy J. Suchomel, Phd, CSCS*D, RSCC

Associate Professor

Carroll University

Waukesha, Wisconsin, United States

Poster Presenter(s)

Author(s)

Purpose: To examine the differences in downward phase durations between stronger and weaker men during traditional (TRAD) and accentuated eccentric loaded (AEL) back squats (BS).

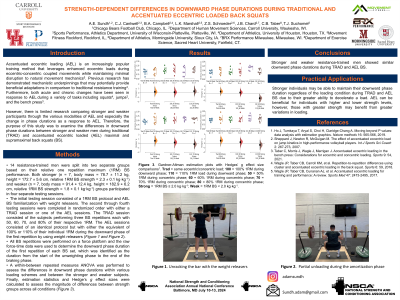

Methods: 14 resistance-trained men were split into two separate groups based on their relative one repetition maximum (1RM) BS performance. Both stronger (n = 7, body mass = 78.7 ± 11.2 kg, height = 172.7 ± 5.6 cm, relative 1RM BS strength = 2.3 ± 0.1 kg·kg-1) and weaker (n = 7, body mass = 91.4 ± 12.4 kg, height = 182.9 ± 6.2 cm, relative 1RM BS strength = 1.8 ± 0.1 kg·kg-1) groups participated in four separate testing sessions. The initial testing session consisted of a 1RM BS protocol and AEL BS familiarization with weight releasers. The second through fourth testing sessions were completed in randomized order with either a TRAD session or one of the AEL sessions. The TRAD session consisted of the subjects performing three BS repetitions each with 50, 60, 70, and 80% of their respective 1RM. The AEL sessions consisted of an identical protocol but with either the equivalent of 100% or 110% of their individual 1RM during the downward phase of the first repetition by using weight releasers. All BS repetitions were performed on a force platform and the raw force-time data were used to determine the downward phase duration of the first repetition of each BS set, which was identified as the duration from the start of the unweighting phase to the end of the braking phase. A within-between repeated measures ANOVA was performed to assess the differences in downward phase duration between various loading schemes and between the stronger and weaker subjects. Hedge’s g effect sizes were calculated to assess the magnitude of the differences between strength groups across all conditions.

Results: Descriptive statistics are displayed in Table 1. During the TRAD condition, there was a significant main effect difference for load (p< 0.001) but no strength main effect (p=0.310) or load x strength interaction effect (p=0.810). During the 100% AEL condition, there were no significant differences for load (p=0.156), strength (p=0.639), or load x strength interaction (p=0.985). However, for the 110% AEL condition, there was a significant main effect for load (p< 0.049) and an interaction effect (p< 0.049) but no strength effect (p=0.449). Except for the AEL 110-60 condition, Hedge’s g effect sizes were trivial-small between the stronger and weaker groups across conditions.

Conclusions: Stronger and weaker resistance-trained men showed similar downward phase durations during TRAD and AEL BS. PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS: Stronger individuals may be able to maintain their downward phase duration regardless of the loading condition during TRAD and AEL BS due to their greater ability to decelerate a load. AEL can be beneficial for individuals with higher and lower strength levels, however, those with greater strength may benefit from greater variations in loading.

Acknowledgements: None